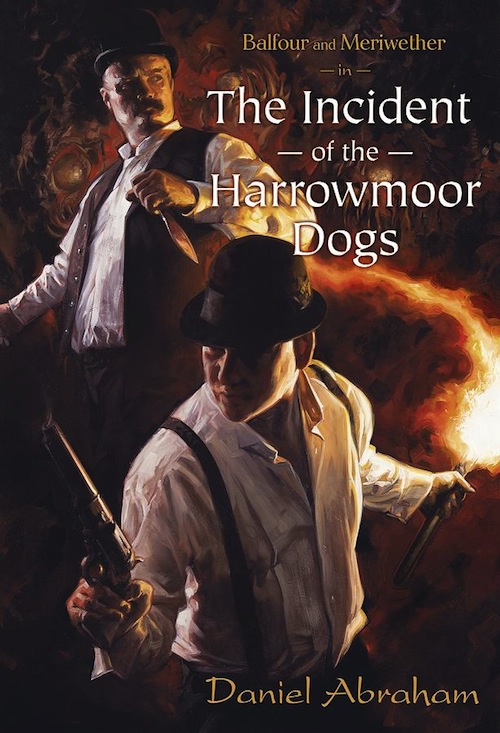

Check out Balfour and Meriwether in the Incident of the Harrowmoor Dogs, the first novella-length work in the Balfour and Meriwether stories by author Daniel Abraham. Available October 31st from Subterranean Press.

When a private envoy of the queen and member of Lord Carmichael’s discreet service goes missing, Balfour and Meriwether are asked to look into the affair. They will find a labyrinth of dreams, horrors risen from hell, prophecy, sexual perversion, and an abandoned farmhouse on the moors outside Harrowmoor Sanitarium. The earth itself will bare its secrets and the Empire itself will tremble in the face of the hidden dangers they discover, but the greatest peril is the one they have brought with them…

London in springtime can be a thing of unsurpassed beauty. The air this morning was crisp as a new-plucked apple, and as I sit here in the gardens waiting for my tea, the sun is as warm as an old friend. From the house, I hear the sounds of the new wireless that Julius and Ethel brought me when last they had returned from India, and a not a moment ago, a group of young men came racing down the street on bicycles, voices raised in laughter and the bluff tones peculiar to masculine companionship. On days such as this, the world seems a wholesome place. And so it is, in part. But only in part.

Nature in her vastness and variety produces both the straight branch and the gnarled, the noble lion and the innocent lamb and the monstrous serpent. I know only too well that the young men of England, fresh of face and broad of shoulder, share the Earth with other beings equally the products of Nature but informed less by Christ than by His eternal enemy. And in all my years of work with Mr. Balfour, and despite my unshakable faith in him, there remains one secret to which I alone am privy…

— From the Last Notebook of Mr. Meriwether, 1920

CHAPTER ONE

The Inverted Man

It was the twenty-eighth of April, 188- and a day of warmth, beauty, and commerce in the crowded streets of London, but Lord Carmichael’s features had a distinctly wintery aspect. He stood by the front window of the King Street flat, scowling down at the cobbled streets. The snifter of brandy in his left hand was all but forgotten. Behind his back, Meriwether caught Balfour’s gaze and lifted his eyebrows. Balfour stroked his broad mustache and cleared his throat. The sound was very nearly an apology. For a long moment, it seemed Lord Carmichael had not so much as heard it, but then he heaved a great sigh and turned back to the men.

The flat itself was in a state of utter disarray. The remains of the breakfast sat beside the empty fire grate, and the body of a freshly slaughtered pig lay stretched out across the carpeted floor, its flesh marked out in squares by lines of lampblack and a variety of knives protruding from it, one in each square. Meriwether’s silver flute perched upon the mantle in a nest of musical notation, and a half-translated treatise on the effects of certain new world plant extracts upon human memory sat abandoned on the desk. Lord Carmichael’s eyes lifted to the two agents of the Queen as he stepped over the porcine corpse and took his seat.

“I’m afraid we have need of you, boys,” Lord Carmichael said. “Daniel Winters is missing.” “Surely not an uncommon occurrence,” Meriwether said, affecting a lightness of tone. “My understanding was that our friend Winters has quite the reputation for losing himself in the fleshpots of the empire between missions. I would have expected him to have some difficulty finding himself, most mornings.”

“He wasn’t between missions,” Lord Carmichael said. “He was engaged in an enquiry.”

“Queen’s business?” Balfour said.

“Indirectly. It was a blue rose affair.”

Balfour sat forward, thick fists under his chin and a flinty look in his eyes. Among all the concerns and intrigues that Lord Carmichael had the managing of, the blue rose affairs were the least palatable not from any moral or ethical failure—Balfour and Meriwether understood the near-Jesuitical deformations of ethics and honor that the defense of the Empire could require—but rather because they were so often lacking in the rigor they both cultivated. When a housewife in Bath woke screaming that a fairy had warned her of a threat against the Queen, it was a blue rose affair. When a young artist lost his mind and slaughtered prostitutes, painting in their blood to open a demonic gate, it was a blue rose affair. When a professor of economics was tortured to the edge of madness by dreams of an ancient and sleeping god turning foul and malefic eyes upon the human world, it was a blue rose affair. And so almost without fail, they were wastes of time and effort, ending in confirmations of hysteria that posed no threat and offered no benefit to anyone sane. Meriwether took his seat, propping his heels on the dead pig. As if in response, a bit of trapped gas escaped the hog like a sigh.

“I am surprised Winters would involve himself in such a thing,” Meriwether said. “He always struck me as being more the sort of man that concerned himself with fisticuffs, opium, and women of negotiable virtue. I have a hard time imagining him wading through the ectoplasmic fantasies of underemployed ladies after greater mystical truths.” “Spiritualist twaddle,” Balfour said.

“It was as a favor to me,” Lord Carmichael said. “Tell me, gentlemen. What do you know of Michael Caster?”

“The explorer?” Balfour asked, his eyes narrowing.

“The very one,” Lord Carmichael said.

“We know what everyone would, I suppose,” Meriwether said. “He was a great hero against the Zulu under Lord Chelmsford, and after his victories in Africa spent some years with the Royal Society. I have his account of seeking the roots of the Prester John and his monograph on the source of the Nile. He also put out several volumes of quite decent poetry. Is he involved in this too?”

“A year ago, Caster had something of a nervous fit. Very little was made of it in the press, thank God. He retired to Harrowmoor Sanitarium for the rest cure, and he’s been there ever since. Last month, he submitted a collection of sonnets for publication. Some references in them seemed to imply a greater knowledge of certain sensitive projects than Caster could be expected to possess. Winters was back from the Russias and I thought I could keep him sober for a few days more if he went to enquire. He left for Harrowmoor at the beginning of the month. His last report, such as it is, arrived nine days ago.”

Lord Carmichael pulled a folded scrap of paper from his pocket and held it out. Balfour stretched out a thick-fingered hand and plucked it away. The paper hissed as he unfolded it. His gaze shot along the lines of crabbed script and inkblots. His eyes widened.

“Delirium tremens?” the thick man suggested, handing the letter across to Meriwether.

“Perhaps,” Lord Carmichael said and sipped his brandy. “I sent to him at once. There has been no reply, and the couriers I have commissioned since cannot find him. I need you boys to pop over to Harrowmoor and see what there is to be seen.”

“A buried and bestial England,” Meriwether said. “A prettier turn of phrase than I expect from our constitutionally discontented Winters. I don’t imagine you have any thoughts what it might signify?”

“I’m afraid I can’t say.”

Balfour let out a grunt. Meriwether, agreeing, handed back the letter. “There’s more than one way to unpack that answer, old friend.”

“There are some aspects of this I’m not at liberty to discuss, even with you,” Lord Carmichael said. “Just find what’s happened to Winters and bring him back if you can. And also, for the love of Christ, why is there a pig carcass on your floor?”

It took the better part of the afternoon to bring their affairs in London into a condition that they might be safely let stand for a fortnight. When near twilight, Balfour and Meriwether stepped out to the street, Lord Carmichael’s carriage awaited them. Meriwether’s paired revolvers were obscured by the volume of his greatcoat, and Balfour’s brace of knives were little more than irregular bumps in his vest, invisible to all but his tailor. The men nodded to the driver, took their places within the carriage. They lurched into the street to the rough music of hooves, wheels, and cobblestones. Balfour stared out the window as Meriwether tapped a gentle fingertip tattoo against his own knees. The sense of dread between them would have been invisible to any other man, but they were more than cognizant of it.

“Winters is a cad with the style of a bawdy house and the manners of a bulldog,” Meriwether said. “I wouldn’t give him a penny I needed repaid.”

“Competent, though,” Balfour muttered.

“One of the best. I’m afraid we may find more at the end of this than too much vice and too little restraint.”

“Know when we get there,” Balfour said, but his manner was agreement enough.

At the station, they strode past the crowded plaforms of London and stepped into the private car arranged for their use. Meriwether lit a pipe against the stink of coal smoke and oil, and with the fading rays of the sunset, the train pulled out from the station and proceeded into darkness.

Harrowmoor stood on a low cliff at the edge of the sea. It boasted fewer than three hundred souls in the town itself, and perhaps as many again eking out rough lives among the low, treeless hills. The landscape seemed to flow out behind the town itself like an unending shawl draped on the shoulders of the buildings as they stared out at the cold sea. The train station was illuminated by a single lantern in the hand of a venerable stationmaster, and Balfour and Meriwether stepped down from their car into the deep and moonlit night with a sense of profound isolation. In London, gentlemen would still be drinking and smoking cigars in their clubs, but Harrowmoor lived by a different clock. The distance between the two habitations of humanity was as profound as if the pair had stepped onto the coldly shining moon. The frost-haired stationmaster ambled to them, his skin colorless in his lamp’s dim light. His eyes were wide-set, and even when he smiled, the thick, sluggish lips had something of the fish in their aspect.

“Gentlemen,” he said, bobbing his head. “I hope the trip was pleasant.”

“Quite,” Meriwether said. “And our thanks to you, my friend, for staying up to meet us.”

“Always do,” the stationmaster said. “Most nights, we don’t see anyone on the last train, but those times we do, it’s best that someone meets them. Wouldn’t want strangers getting lost. Not at night. You’re for the sanitarium, yes?”

“Come to visit, yes,” Meriwether said.

“Of course, of course,” the old man said, turning toward the street. “You two gentlemen don’t have the consumption. I’ve seen them come and I’ve seen them go, and I can tell. Better than the nurses, I am. Only takes a look, and I can say whether a man’s too far gone. No mysteries left for me.” He let out a rasping chuckle like a rusted clockwork.

“I understand our cousin preceded us,” Meriwether said, trotting to keep pace. “Perhaps you might have met him as well?”

“If they come by train, I see them.”

“Young man,” Balfour said. “Brown hair, pale eyes. Scar across the back of his left hand.”

The stationmaster shook his head. “Nonesuch by land. Might have come by water, though. Some do.”

The street beyond the train station was narrow and black. The stars overhead shed too little light, and rather than dispelling the shadows, the ruddy lantern made them seem deeper. A squat building stood on the near corner, the light and scent and soft mutter of voices marking it as a public house. A sign hung before it was rendered illegible by the darkness.

“Here’s the Black Hound, gentlemen. Best lodging in Harrowmoor, the sanitarium notwithstanding,” the stationmaster said with a wheezing chuckle. Meriwether turned back. The lit carriage windows of the train sixty feet away shone brighter than the slivered moon.

“It seems a short enough walk to make unchaperoned,” he said.

“Like it does, sir,” the stationmaster said. “But men get turned around in the dark sometimes, and we’re not far from the moorland. Will-o-the-wisps sometimes too. Lead men where they oughtn’t be, and that’s not good. Safer this way is all. Safer.” He nodded to himself as if impressed by his own wisdom.

Meriwether drew a coin from his pocket and pressed it into the old man’s palm. The fishy eyes went wide when they caught the metal’s color.

“My thanks,” Meriwether said. “Really, you’ve been more than kind. I was wondering if you might know something of the man we’ve come to see.”

“Kind of you, sir, but I haven’t seen your cousin—”

“Not him,” Meriwether said. “We’ve come to interview a famous explorer and war hero. His name is Michael Caster.”

The stationmaster’s face shifted, deforming into a comic mask of disgust. His scowl was so profound, the corner of his mouth seemed to droop almost past the line of his jaw.

“That one? Yes, I saw him when he came through. Would have been about a year ago now. Strong fellow. Wide across the shoulders. Smoked them black Turkish cigars. Oh, yes, I remember that one.”

“We’ve not met him,” Meriwether said. “Not yet. Anything you could tell us that would be of use would be appreciated.”

The stationmaster glanced at the coin in his hand, then slid it into his pocket with a sigh. “We see a fair number come up to the sanitarium. Consumption. Nerves. Women with hysteria or the cancer. Men with them sicknesses they catch from women on the continent. All sorts, and I ain’t one to judge. Not the sort of man I am, but that Mr. Caster of yours? I met his train too, and I’ll tell you this for certain. What’s wrong with him can’t be fixed.”

The pub’s mistress was a thick-featured and sullen woman who took as little time as possible in greeting them, seeing them fed bowls of roasted chicken and overcooked beans, and sending them off to their room. Meriwether’s gentle and probing questions concerning Winters could as well have been asked to a stone. The accommodations were close and rusticated, with a single bed and rushes on the floor like something from Chaucer. A gentle sobbing sound passed through the thin walls from an adjacent room, and the awareness that their privacy was compromised brought their conversation down to whispers as they took turns making their ablutions at the small basin.

“Charming place.”

“It isn’t the last word in luxury or hygiene, that’s true, but you must agree is has its own distinctive style. The combination of crushing poverty and gleeful judgment of others speaks of rural England at its most morally supine. A perfect example of its species, I’d say. The very epitome of things best left uncelebrated.”

Balfour grunted, pulling off his boot, then drew the hidden blade from its seam. The candlelight danced along the well-oiled steel, and the mustached man returned it to its sheath with a sense of satisfaction. Meriwether laid his own weapons out on the bed cover, deftly disassembling and reassembling the revolvers as they spoke.

“Winters and Caster,” Balfour murmured.

“The former must have taken lodging somewhere, and is, after all, the subject of our proximate investigation. It is even possible that his disappearance bears less on this present enquiry than on some other business with roots sunk half around the globe and which only happened to bloom here and now.”

“Can find Caster, though.”

“It is a point in his favor that Michael Caster has fallen where there is light,” Meriwether said. “And if Winters did interview the man, it’s more than possible that Caster may know something of what preceded the disappearance. So which scent do we follow? The hunter Winters or the man Caster whom he hunted?”

Balfour hung his vest on the back of a chair and began pulling his blades one by one, testing each edge as he did. In his shirtsleeves, his body seemed a solid knot of muscle. Meriwether finished reassembling his pistols and slid them back into their paired holsters. There was not so much as a drop of oil to mar the bedding where he had worked.

“Both,” Balfour said.

“I had drawn the same conclusion. I will repair to the sanitarium in the morning if you like and leave you the task of tracking down word of Winters here in the town.”

“No difference to me,” Balfour said.

“You are an eminently agreeable man,” Meriwether said, and both men smiled at the joke. “Is there anything in this present matter on which you do have a preference?”

“First watch,” Balfour said, “and the side against the wall.”

The sanitarium stood half a mile out from the town, but the road to it was solid and well-maintained. The white walls rose above the bare landscape like the bones of the earth itself. Seagulls wheeled in the white sky, calling mindlessly to one another. To the east, the sea stretched grey and uneasy to the horizon, to the west, the moor rolled, hill after low, scrub-choked hill, and Meriwether would have been hard pressed to say whether land or sea bore the more forbidding aspect. Only the scattering of trees that rose above the sanitarium walls hinted at some other world within, a secret garden inaccessible as Eden denied. The nurse who greeted him stood half a head below him. Her uniform was a blinding white that was meant, he felt sure, to indicate purity and health, but left Meriwether thinking in vague and unpleasant ways of sterilization.

The interior of the sanitarium surrounded a courtyard. Half a dozen men sat on chairs beneath the boughs of stunted oaks. The youngest of the men looked hardly more than a boy, his skin the color of fresh-turned clay. The oldest of them, his hair reduced to wisps and his skin a map of cavernous wrinkles, had half-closed eyes and brown lower teeth exposed by his gaping jaw. If it was Eden, it was one peopled by the lepers hoping for the Savior’s kind hand. Meriwether felt the growing certainty that few of the sanitarium’s patients were destined to leave.

The chief physician’s office looked out over the courtyard, but was not so high as to see over the sanitarium’s outer wall. The effect was of a beautiful and well-tended world that stopped suddenly. Glassed cabinets displayed a variety of medical equipment, a menagerie of steel and vulcanized rubber. The man himself was thin as a weed with dishwater blond hair slicked back over protruding ears. He stepped from his desk with his hand extended.

“Mr. Meriwether! Come in, come in,” he said in a quacking American accent. “Any friend of Lord Carmichael is welcome here. Take a chair. Can I offer you a cup of tea?”

“I appreciate the offer, but…”

“All right. Your choice.” The physician dropped back into his seat with a grin, like a child at Christmas.

Meriwether crossed his legs. “I’ve come to enquire about a patient of yours. Michael Caster.”

“Yes, of course. Hard one. Nervous excess. Aberrant, self-destructive behavior. It was his uncle who got him here, bless the man. Became concerned that Michael would do himself permanent harm. He’s been with us for almost a year now.”

“Self-destructive behavior?” Meriwether prompted.

“Very much so,” the physician said. “Yes, indeed, very much so.”

When it became clear that no further details would be forthcoming, Meriwether changed tacks. “Has his condition improved since his arrival?”

The physician leaned forward, his fingertips pressed to his bloodless lips. “Truth to tell, I can’t say he has. He’s changed plenty. When he first came, he was angry all the time. Lashing out. We had to sedate him for most of June, but once that course was complete, the violence of his outbursts lessened. He’s calmer now, but with nightmares five, six times a week. And his underlying condition… No, sir, I’d love to tell you he’s getting better, but I’d be lying.”

“I understand he has been publishing poetry?”

“Yes, I’ve allowed him—encouraged him, even—to express himself through his work. It seems to give him some relief, but as a long-term therapy, it isn’t having the effect I’d hoped. He works, and some of his compositions are quite memorable, but there’s a darkness in them that only seems to be growing. His outward demeanor is pleasant enough, but I can’t say we’ve plumbed the depths of this. Not at all.”

“His long-term prospects are bleak, then?”

“Wouldn’t say that,” the physician said. “We have a lot of tools in our chest we haven’t pulled out yet. Aversion, chemical therapies. There’s some fascinating work with direct manipulation of the living brain being done back in Ohio that holds promise. He’s a brilliant young man, and we’re a long way from giving up on him.”

“May I meet with him?”

“Of course,” the physician said. “I think he’d like that. He was very pleased when that last fellow came. Winters?”

“Yes,” Meriwether said, rising to his feet. As they stepped toward the doorway, he paused. The physician looked back at him, inquiry in his expression. “Does Mr. Caster do his work in his room?”

“The writing you mean? He does.”

“Might I have a moment in there alone before our meeting? I’ve found I can learn a great deal about a man by the way he lives and works.”

The physician blinked like an owl, then shrugged. “Can’t see any reason not to. If you find something that could give me some insight into the fella, you’ll pass it on.” It was phrased almost as a request. Meriwether had the sense that the chief physician was unaccustomed to having his will questioned.

“Of course,” Meriwether said. “Lead on, and we will find what can be found.”

The room was small and neatly kept. White plaster walls rose above the simple bed and small working desk. Three leather-bound notebooks rested beside a stub of pencil, charcoal, and a rubber eraser. The sheets were folded with precision, and the chair at the desk stood neatly in its place. Meriwether held out both his arms, fingertips just brushing the opposing walls. The space itself reminded him of a monk’s cell, peaceful and clean and utterly divorced from the world. He ran his hands along the bedclothes, but no secret items disclosed themselves. The flat pillow held nothing but a few handfuls of limp feathers. Sharpened iron bars bloomed from the windowsill, preventing birds from roosting and inhabitants from leaving with equal facility. The chief physician haunted the doorway, bouncing slightly on the balls of his feet, as if in anticipation of some discovery, some new chink in his patient’s psychic armor.

Meriwether picked up the notebooks, thumbing through the pages slowly, carefully. The script within was legible and controlled. Even on those pages, and there were several, where the author had been struggling with the scansion of some particular phrase, it was done with the precision and regularity of a draughtsman. In among the poems and notes, there were also sketches rendered in pencil and coal. Most had the precision and beauty of anatomical studies: a tree standing along the side of a page with the texture of bark and leaf made clear, the study of a beetle in all three planes, and even the room in which Meriwether now stood as seen from the bed. They were technically admirable and displayed a profound if analytical sensitivity, and Meriwether expected much the same of the poems until he reached the third notebook. Here, the images became stranger and more phantasmagorical. Strange beasts, half hound and half insect, stared out from the pages, vicious teeth snapping. And then another image, a single sketch which stood out from the others.

t was of a young man in his shirtsleeves, fair-haired with the faintest of smiles pulling at the soft charcoal lips. The figure wore trousers high on his waist and rested on one hand as through he were leaning against a wall. The masculine gray eyes were fixed upon the viewer, and Meriwether felt his eyebrows rise and his heart step up its pace in surprise. And indeed shock. The man depicted was unfamiliar, but his pose and intent could not be mistaken. He was powerfully beautiful, the apotheosis of the masculine animal. All he knew of Michael Caster came into a sudden new perspective.

“Ah, guests then,” an unfamiliar voice said. “Please don’t wait for my permission. Make yourselves at home.”

Michael Caster was the human embodiment of his room. Light brown hair cut neatly and close to the neck. His build was trim and athletic, and the rage at their invasion of his privacy hardly showed in his sky blue eyes. His shirt was the same white as the nurses’ uniforms, but on him, it spoke more of an unpainted canvas awaiting the artist’s stroke. His trousers were dark and ill-fitting. They were the sort that the other patients wore, likely all laundered together and returned afterward to whomever was in need. A uniform for the damned. He seemed too young to have served in the Zulu wars, but when Meriwether looked closely, the signs were there. The first dusting of gray at his temple, the places where his skin though still unmarked would show one day a permanent crease. Meriwether put down the notebook.

“Now Michael,” the physician began, “you know that—”

“I apologize,” Meriwether said. “The intrusion was at my request. I’m afraid I may have let your status as a patient distract me from the constraints of courtesy. The fault is mine.”

Caster lifted his chin as if hearing an unfamiliar sound. Something between amusement and distrust plucked at his lips.

“Mr. Meriwether’s come to speak with you, Michael.”

“If you don’t mind, of course,” Meriwether said.

“Anything to shake up the monotony, I suppose,” he said carefully. “I will have to check with my social secretary, but I believe I was slated to be here the whole day. I get out so rarely, you know.”

Meriwether turned to the chief physician with a polite smile. “Thank you very much for all your help in this. Lord Carmichael will be very pleased.”

The dismissal was so polite that for a moment the physician didn’t understand it had been delivered. His eyes widened for a moment and then a pale smile drew back his lips. He began to speak, stopped, nodded to both men and stepped away holding his head high. Caster chuckled low in his throat.

“He won’t thank you for that,” Caster said. “The good doctor is unaccustomed to being excluded.”

“It will be good practice for him, then,” Meriwether said, then took a breath and plunged at once to the vulnerable point. “I was led to understand that you came to the sanitarium after a fit of nerves. That isn’t true, is it?”

“No.” Caster crossed his arms. His gaze shifted onto the blankness of the wall.

“You are inverted. A homosexual.”

“I…am.” The man’s voice moved slowly, carefully, picking its way among the syllables as if they might bite. “Not that I see it is any of your concern.”

“It is what brought you here, however?”

“It was,” Caster said. He held his body square as a man before the firing squad. “I was involved with a younger man. It was unwise and rash, but I was very much in love. His father discovered us, and my uncle, soul of Christian charity that he is, arranged for my indefinite incarceration here rather than commending me to the law. If you have some judgment or comment you’d like to share about that, I cannot prevent you.”

“It’s no concern of mine,” Meriwether said. “I’ve come looking for Daniel Winters. He’s gone missing.”

Caster’s gaze returned, his eyes flashing with concern. “God. Missing? How long?”

Meriwether pulled out the desk chair and sat, his fingers wrapping his knee.

“We had word from him two weeks ago, but it wasn’t particularly coherent. Since then, nothing.”

“He’s gone to them,” Caster said.

“Gone to whom?”

“The dogs. The ones in my dream,” Caster said. Then caught himself and shook his head, “And here you might not have thought I was mad.”

“Perhaps it would be best if we began at the beginning,” Meriwether said.

“The whole sordid tale?” Caster asked, stepping forward to lean against the foot of the bed. Meriwether felt himself smile almost against his will.

“Perhaps an abridgment. What did you and Mr. Winters discuss? What are the dreams you speak of, Mr. Caster, and when did they begin?”

Caster sat on the bed’s edge, collecting his thoughts for a moment.

“I am not a superstitious man. I don’t believe in things without some evidence to support them. When I tell you that I have always been led by my dreams, I hope you will understand it is because my dreams have been a curiously reliable guide. In Africa, I knew of the coming attacks days before they transpired. Sometimes I would even know the number of the enemy, the direction from which they would come, and the time the assault would begin. I’m not a fool. I never relied on the dreams being accurate. I only prepared in case they were, and more often than not, it was good that I had. I suspect that many of the men in my mother’s family suffered the same effects. Something in the blood, I suppose. I became used to them. A sort of useful party trick, and nothing more. And then, I came to Harrowmoor.

“From my first night here, I have been plagued by nightmares. They are not always identical, but in some details, they remain consistent. Always, I am in a barn near an abandoned farmhouse. It is always twilight, the sunlight failing around me. And there is something like a well. An ancient stone shaft into the earth with walls made from stones like those of a henge, only sunk deep into the earth rather than resting upon it. I know, in the dream, that the barn was built around the well, that humanity discovered this and thought nothing more of it than a convenient place to cool milk and meat. My mind descends into the darkness. There is a world down there. Lightless, but not unpeopled. Vast cities and warrens of passages too narrow and close for the human form. It is as if a great empire had flourished beneath the earth. Passages lead not only throughout England, but under the seas to strange and foreign lands. And deeper too, leading to places where the cooling air grows hot again, and lichens and fungi feed upon the sulfurous warmth with a sluggish awareness that is almost like animal life. I feel this vastness more than see it. I experience it as you might know the state of your own body. Great beasts sleep there, and strange intelligences battle in lightless subterranean wars. I have seen things that no waking eye has ever seen. Parasite worms that dig into the living flesh of their enemies and swallow up the brains, then use the corpse as a mechanism, riding it as you or I might sit a horse. Toothed grubs that chew their mindless way through basalt and brimstone, weakening the foundations of the world itself. And the dogs. Always and without fail, the dogs.”

Caster’s face grew drawn, his cheeks seeming to sink into his face, his eyes darkening and becoming hollow. Absently, he rubbed his fingers together with a sound like paper sliding against paper. “I call them that, but they have other names for themselves. They are no larger than wolves, but they possess minds of great complexity and insight and terrible, vicious purpose. Once, I believe the great underground empire may have had a thousand species that flourished in that uncanny darkness. A world below the world, if you can imagine it. It is a second, dark and cthonic world warmed from below as we are warmed from above, our shadow and our twin. Most of its inhabitants have been consumed or slaughtered, and those that remain do so because they are of use to the dogs. In the dreams, I am among them, and they know me. They can smell the traces of my dreams, and they try to follow me back. I know that if I lead them to the surface of the world, they will find me. Here, in this room, Mr. Meriwether, they will find me. And my life would be forfeit. And so I flee deeper and deeper into the underground, and the dogs follow, howling.”

“Your drawings,” Meriwether said. “They are of these dogs?”

“Mr. Winters asked the same thing. Yes. Those are the beasts from my dreams.”

“And they are what brought him to you? I understood there was a poem.”

“I have a friend in London who keeps a little salon. He collects people he finds interesting. Poets, artists, men of science and politics. It is more innocent than it sounds. He puts together a small broadsheet when it amuses him to do so and distributes it among his circle. He and I exchanged letters for a time. I sent him something I had written that mentioned the underground empire. I didn’t know anyone else had seen it until your Mr. Winters appeared one day and asked about it. What had inspired it, what I knew, and how I knew it.”

“And you said?”

“What I have told you, more or less. He asked for specifics of the farmhouse. The barn. I guessed that he intended to seek out the places from my dreams as if they were real. I warned him against it, and I thought at the time I had persuaded him. But perhaps not. He’s found it, then? He’s gone down?”

Meriwether leaned forward.

“We don’t know,” he said. “He has vanished, and we have come to find what we can to explain it. Knowing Mr. Winters as I do, he may have found a brewery whose wares he particularly enjoyed or a woman with a particularly fetching smile.”

“But you doubt it,” Caster said. “Don’t you?”

“My companion is looking for him now. I have the greatest faith that whatever can be found out will be.”

Caster shook his head. “Don’t let him go underground. If the trail leads there, let it go. You’ll have lost one man, but better that than two. Or three, I suppose.”

“Mr. Balfour and I have faced many dangers,” Meriwether said. “I have no doubt—”

“Nor have I, sir,” Caster said. His voice was hard as stone. “You’ve come seeking what I know? I know that very little which falls into that dark pit returns again to the light.”

A variety of witticisms presented themselves to Meriwether’s tongue, but he spoke none of them. Caster’s expression was so serious and bleak that to treat his concerns lightly would have been rude. Instead, he stood. A pigeon fluttered close to the window and then away, covering Caster’s face for a moment with the shadow of its wings.

“Thank you for your time and attention, Mr. Caster,” Meriwether said. “I think perhaps I should seek out my companion and apprise him of your advice.”

Caster’s smile was thin and haunted. “I think you should run, Mr. Meriwether. But before you do, may I ask you a question? As a man of the world?”

“You may.”

“You divined the reason for my interment here. They have discussed a great number of treatments for me. Most recently, they have considered unmanning me surgically and giving me a course of forced sedation that would last the rest of my life, however long that might be.”

Meriwether locked his hands behind him. “I have heard some such discussion, yes. But you said you had a question. That was a series of statements.”

Caster nodded. “I did not ask to be what I am, nor did I choose it. As a man of the world, do you consider my inversion a disease to be cured?”

“No,” Meriwether said at once. “I am a servant of crown and church, and I take my guidance from them. Homosexuality is no disease. It is a sin and an abomination.”

Pain flickered in Caster’s visage, and then a careful smile. How many years, Meriwether wondered, had the man practiced the art of appearing not to care?

“I am as God made me,” Caster said.

“I see no contradiction,” Meriwether said. “God makes many abominable things, and I am in no position to condemn His choices. But now, sir, you must excuse me. I have other monstrosities to attend to.”

CHAPTER TWO

Voices From the Deep

After leaving Meriwether’s company in the morning, Balfour began with a leisurely walk through the town. His first impulse in times like these was toward violence and threats, and so it was only through an act of will that he restrained himself from direct action. Before the campaign could begin in earnest, it was best to know the battlefield. He strode through the dark streets with his nearest approximation of joviality, his eyes shifting constantly from face to face, from building to building, without seeking any one thing in particular. And so he allowed himself the luxury of building a sense of Harrowmoor Town, and with it a better idea of where his efforts might be properly placed.

In daylight, some part of the town’s grim aspect disappeared, but only some. The clay of the earth itself held a grayness that seemed to have worked into the skin of the townsmen. The children laughed and played in the streets just as they did in any such place, but their chants and whistles had a cruel undertone. The horses that pulled the carts down the streets had an empty exhaustion in their eyes that recalled men too long in battle who had become inured to the trauma of their surroundings. Soul-dead. There were neither cats nor dogs anywhere in evidence. Balfour’s own presence elicited neither curiosity nor remark. The trade of the sanitarium, he supposed, would bring a steady stream of odd and grieving humanity to Harrowmoor. He might have been a physician come to consult about a difficult patient or a man with a consumptive wife dying by gasps upon the far hill. The townsmen would be accustomed to strangers passing through. Perhaps so much so as to be blinded to them.

As he stepped into the small market square with its half dozen rickety stalls and sun-bleached awnings, he found himself wondering how many men had died in the sanitarium, and whether the concentration of so much suffering and death might somehow have poisoned the land itself. Or possibly the moorland had always carried a sense of doom and disquiet, and so become the natural home of the hopeless and dying.

He shook himself, trying to shrug off the malaise that threatened to overcome him as well. He hadn’t come to ruminate upon the effects of mortality on the landscape. He was here to find Winters, or if not the man, at least his track. He scanned the stalls and streets, willing himself to see them not only as he did, but as his prey might have. A white-haired crone stood at a stall, a basket of eggs before her. At another, a thin man with a tremor in his hands shooed flies away from a display if disreputable-looking meat pies. Two young toughs leaned against the wall at the mouth of a bright alley hardly less dignified than the street it opened upon. The boys were caught between leering at a young woman walking down the sidewalk and embarrassment at their own lust.

“If I were Winters…” Balfour said to himself. Then he quirked a smile. The question was not only what Winters would have done, but who would have noticed him doing it. For that, the solution was obvious. He stroked his mustache in satisfaction and trundled across to the two young men. The boys scowled at him and pretended to look away until his focus and intent were impossible to ignore.

“You there,” he said. “I’m looking for a man was here a few weeks back.”

The taller of the two youths had lank, dark hair and a rot-brown front tooth. His shorter companion was still taller than Balfour with sand-colored hair and a weak attempt at a beard.

“Lots of men come through,” Rot-tooth shrugged. “Don’t matter to us.”

Unfortunate Beard pulled a worn work knife from his boot and began cleaning his fingernails with it. Balfour felt a wave of pleasure as he plucked it from the boy’s unpracticed hands. Unfortunate Beard’s eyes narrowed in anger until Balfour shifted his vest, displaying his brace of knives, and then they went wide.

“This would have been a gentleman in his thirties. Dark hair, light eyes. Handsome and a bit full of himself. Scar across the back of his hand. Would have made propositions to any girl in town whose heels looked even slightly rounded. Now, my guess is you boys are more aware than anyone else what men are talking to which girls. And so I think you know who I’m speaking of. Yes?”

The two looked at each other. Their uncertainty spoke volumes.

“What’s he to you?” Rot-tooth asked. Balfour hardly had to consider which lie to tell.

“He’s a friend of my wife’s,” he said coldly, and let the knives and implications speak for themselves. It took little time for the boys to imagine bloody vengeance taken upon their imagined sexual rival. As though they were anywhere near Winters’ league.

“Right, then. We’ve seen him. Stayed in the Black Dog for a week, then started out for the moors.”

“The moors?”

“That’s right. Walked all over them, night and day. Probably got caught in a bog.”

“Last I heard,” Unfortunate Beard said, “he was staying at the old Phillips place. Farmhouse halfway to Fenton. No one’s lived there since old man Phillips died of the cancer and his daughters lit out for the colonies.”

Balfour smiled and handed back the worn knife, handle first. Unfortunate Beard took it.

“Don’t suppose you fine gents could give me directions,” Balfour rumbled, his voice a graveled mixture of pleasure and the threat of violence. “And then see to it that no one mentions to our mutual friend that anyone’s looking for him.”

Half an hour’s time later, and still well before lunch, Balfour had an egg sandwich in one pocket, a bottle of beer in the other, and clear directions out through the moorland to the farmhouse where Winters had last been known to abide. He walked with a bit of a spring in his step despite the treeless, grim surroundings, buoyed up by the predictability of jealous young men and randy old ones. Between Winters’ penchant for flirtation and the local adolescents’ resentment of it, Balfour had the thread to walk this unwalled labyrinth.

The sun rose high in the great pale bowl of the heavens, and the moor stood quietly beneath it. Low hills flowed down from the town, the land growing wetter with each new small valley. The whine of insects filled the air with mindless, tuneless song that soon dispelled Balfour’s bright mood. Gorse and wild blackberry grew unchecked beside the paths, their leaves bright and forbidding. It wasn’t until he paused to eat his sandwich and beer that Balfour noticed the little details that had been troubling him. The moor was rich with plants and insects, but no animals seemed to live here. No rabbits had chewed back the brush. No voles or mice fled at his approach. The sense of being utterly alone was as profound as it was uneasing.

The farmhouse, when he found it, was unmistakable both in its identity and its emptiness. Weather had stripped the doors of their paint, leaving the exposed wood to rot. The thatching of the roof sported weeds and wildflowers, and trails of black moss dripped down the walls beneath it. Balfour drew his knives, holding the blades against his wrists in case there should be anyone watching from within the derelict structure. Silent as a cat, Balfour stepped forward. Broken windows stared blindly at his progress. When he eased the door open, the stink of mildew, fungus, and rot assailed him. The soft ticking of insects in the thatch and the groan of floorboards under his weight were the only sounds as he stepped through the modest structure. The rooms were close and the walls sagged at strange and disturbing angles. His intellect told him that once a family had made their home in this place, but his imagination could not encompass the thought. The farmhouse was so profoundly ruined he could only believe it had sprung up already destroyed at the beginning of the world.

In the back room, he found what could only have been Daniel Winters’ camp. A glass lantern stood on a stool, thick yellow oil in its reservoir and soot darkening its glass. A bedroll lay on the floor beside it, threads of mold already creeping across the wool. With the point of one blade, Balfour folded back the cloth, then lifted it. The holes that pierced it were ragged. Torn, then. Not cut. The blood was black, rotten, and copious enough to speak of a superficial wound but not of immediate death. Whatever had taken Winters, it had taken him here. A leather notebook still lay under the pillow alongside a small, brutal-looking pistol. Balfour sat back on his haunches for a moment, then turned the book with a knifepoint, inspecting it carefully before committing his bare fingers to holding it. The writing within was the schoolboy’s scrawl he’d seen on reports from Cairo and Munich, though wider and less controlled. Winters without a doubt. He riffled the pages quickly until the paper went blank, and then went back to the final entries. They were as coherent as the report to Lord Carmichael, and perhaps less.

Yes fiat lux and then we’re buggered. Light is the only hope against these bastards. Empires and then empires. Carmichael’s mad—don’t want a gun if you can’t tell the barrel from the grip, he said, well too right. They can’t get in here, or they’d have by now. Still get the feeling the bloody things are playing with me.

Balfour paged back. There was little that made more sense. Partly, no doubt, was the nature of the document. Had Winters been writing something other than prompts to his own memory, it might have been very different indeed. On the other hand, he’d known his letter to Lord Carmichael had possessed a separate audience. Unless Winters had had some reason for making his correspondence obscure, even to those who might read it legitimately…

Balfour’s head snapped up like a hound scenting a fox. His body went perfectly still, and he waited, his ears straining to recapture the thin thread of sound. It came again. Little more than a trembling of the air. Still, it had not been his imagination. Balfour tucked the notebook in his pocket and reacquired a firm grim on his knives. He moved like a shadow, his senses keen as a fresh scrape. The stink of burnt beans lingered in the still air of the kitchen. The back door stood shattered in its frame. Balfour knelt, considering the mark on the floorboards. The pale mud showed wide marks like a massive dog’s paw, but lengthened at the fore with something like fingers. The sound came again, and there was no doubt this time. It was a human voice, and it was screaming.

The barn stood behind the farmhouse, its blackened timbers stinking of rot. The great door hung open. The shrieks seemed to come from beyond the structure until Balfour moved to its farther side. Then they shifted and seemed to come from the house. It was as if another landscape existed within the confines of the ruined barn, the tortured man lost somewhere much more distant than the frail walls contained. Balfour scowled and made his approach. Within, pillars of light dappled the empty spaces, shining from the holes in the church-high roof. Abandoned stalls showed where cattle had once stood. A ladder still rose up to a hayloft, dust-heavy webs empty and exhausted between the rungs. In the rear of the place, as if squatting in the shadows, a low slab of stone with a gaping square hole four feet to a side at its center. A thick rope led from an iron ring in a stout oaken beam to the edge of the darkness, and disappeared within it. Balfour surveyed the uncomfortable mixture of shadows and light to be certain no attacker lurked to pitch him into the black well before he squatted at its mouth. The screaming was louder here, distinct and specific. And also dreadfully familiar.

“Winters?” he shouted. “Winters, is that you? Can you hear me, man?”

The screaming did not change. Balfour rubbed the back of one hand against his chin. No flicker of light shone in the darkness below, and the sunlight revealed not more than six feet of rough stone before it too failed. Balfour rose to his feet, casting eyes around the darkness.

“Hold strong, man,” Balfour bellowed. “I’m coming down.”

Balfour ran back to the farmhouse, retrieved the oil lantern, and lit it with a match from his own pocket. The thin, buttery light seemed too weak for the powerful darkness of the well, but there was no time to find a better torch. Reluctantly, Balfour sheathed his knives, took the lamp in one hand, and wrapped the rope around the other tightly enough to grip but not so much that he could not choose to let himself slip down. With the physical confidence of a man well-versed in violence, he set feet to stone and began lowering himself down into darkness.

The rock face before him glittered with the damp, and the soles of his shoes slipped more than once, cracking his kneecaps hard against the unforgiving stone. Cool air rose around him, carrying with it the smell of deep earth and perhaps something else: a rough and acrid stink like rancid piss. The effort of the descent made Balfour’s jaw clench so firmly that his teeth creaked with the pressure. The thin flame in the lamp shuddered in the cool air around him, and the gray square of daylight grew smaller and more distant. With every yard, the ache in his arm grew until the muscles began to tremble. Any return to the world of sky and sunlight would require the use of both hands, but the thought of making this transit without the small light he carried filled him with an inexplicable dread.

The vast stones slipped seamlessly past him, defying any thought of mere human construction. No monolith so great had stood beneath the great bowl of the sky, but the mineral vastness of the earth below him seemed at once as vast as the heavens and close as a grave. Winters’ ongoing shrieks did nothing to calm his nerves, but decades of study gave him the mental discipline to peg his fears at mere brusk annoyance. It seemed that the trial might go on forever, the rough hemp sliding around his elbow and across his palm until he reached the doors of hell itself, and then the shaft’s end came into the sphere of light, and Balfour dropped the last few feet.

The ground beneath him was a thick clay that made soft, unpleasant sounds under his feet and pulled at his shoes. Two low tunnels led into the deep earth, lightless as dead eyes. Balfour shook his rope-scraped hand until the feeling returned to his fingers, then plucked a blade from its sheath. The steel seemed brighter than the flame that illuminated it. The tunnels, while almost ten feet across, stood little more than four feet high. To move forward, he would have to bend low and leave at least one of his flanks exposed. Balfour’s mustache quivered with disgust at the tactical situation, but he chose which of the tunnels the screaming seemed to emit from and moved forward. Winters had to be close now. The screams had an exhausted quality, as a body might make when the intelligence controlling it had abdicated, a harsh and mindless sound. The stink was worse here, but he ignored it. The darkness seemed to suck away the light and give nothing in return. Balfour cursed quietly under his breath, and then called out.

“Winters! Stop making that racket. Where are you, man?”

The screaming stuttered, failed for a moment, and then began again. This time with words. “Balfour? Get out! Flee before they find you!”

A chill raced down Balfour’s spine, and he hesitated between moving toward the man’s voice and heeding his warning. With a growl, he turned back, running hunched almost double in the direction of the rope, shaft, and life. The filthy earth squelched under his feet. And under other feet as well. Where Winters’ voice had competed only with silence before, now there was a scuttling as of a million rats. Balfour steadied his grip on the blade.

The five things that blocked his path were not rats. The beasts stood on four legs, the size of hunting dogs with powerful haunches and thin, mobile forelegs. Their pale skins sported scaberous black growths like great, rough scales of a terrible insect. Great jaws hung open, teeth set on the exterior of lipless mouths. Their eyes were massive and black as wet coal, and they held a terrible and alien intelligence. As Balfour stood, waiting to see whether the beasts would attack, the nearest of them chittered, its voice high and cruel and articulated in fashion that carried the impression of speech without the meaning. More inhuman voices came from the deeper darkness. These were the vanguard of some greater force, and Balfour had the sickening certainty that the host was vast.

One of the beasts on Balfour’s left darted forward too quickly for the eye to see. Long-honed reflex brought Balfour’s blade to his defense, but the attack had been a mere feint. The beast jumped back, and two on the right leapt in toward him. He fell back, swinging his razor-sharp blade. The doglike beasts retreated, but not so far as they had been. Balfour knew he was being driven back, but the knowledge redeemed nothing. He was on their territory, encumbered by the weight of stone and earth above him as well as the desperate need to protect the dim and flickering light in his off hand.

Inch by inch, foot by foot, they pressed him into the darkness. Twice, the animals came too near and Balfour’s blade drew forth a yelp of pain and a thick black ichor. Once, his reaction came too slowly, and one of the dagger-like exposed teeth scraped against his shin, coming away pink with his blood. The passage began to slope down behind him, giving the beasts the high ground. He sensed the drop off as a change in the sound behind him. There was neither choice nor hope. He leapt back into the abyss without taking his eyes from his attackers.

His feet struck wet ground not more than six feet from the drop-off’s lip. The beasts chittered among themselves and then fell back into the blackness.

The cell, for there was no other interpretation, was little more than a pit ten paces across. The man who squatted at its far edge had once been Daniel Winters. His skin was pale now, his hair and beard thick with the gray mud. An angry wound stood half-healed across his ribs and welts marked his arms, feet, and throat. An old scar split the back of a filthy hand.

“Well, old man,” Winters said, his voice hoarse and pained, “Sorry to see you here.”

“Sorry to’ve come,” Balfour said. “Thought I was rescuing you.”

“Appears I was bait,” the thin man said with a shrug. “I thought the bastards were tormenting me for the joy of it, or I’d have warned you sooner. They do that sometimes. Torture me for pleasure. And Christ alone knows what they’ve been giving me as food.”

“What are they?”

“Lords of the underworld,” Winters said. “Kings of a dark empire that spans half a continent.”

“Mm.”

Balfour eyed the wall of slick clay at the pit’s edge. Scrambling up it might be possible if one of them gave the other a leg up. At a guess, they were no more than thirty yards from rope and shaft. Near enough that a tortured man’s cries might reach the surface and call down help that could itself be captured.

“I think they won’t return so long as the lantern holds,” Winters said. “They’ve no love of light. They can stand it, but it hurts them. I don’t suppose you’ve brought Meriwether with you as well?”

“He’ll be along.”

“How soon?”

Balfour considered. The prospects of a good outcome seemed dim indeed. He placed the lamp gently onto the ground, stepped back, and lifted his wide hands to his mouth in a rough speaking trumpet.

“Don’t come down!” Balfour bellowed. “It’s a trap! Don’t come down!”

“He’s up there, then?”

“Will be eventually,” Balfour said, and resumed his deep-throated bellow, “Meriwether! Don’t come down!”

Winters’ chuckle was devoid of anything like real mirth. “How long do you think you can keep that up, old man?”

“Lifetime, I suppose,” Balfour said.

Balfour and Meriwether in The Incident of the Harrowmoor Dogs © Daniel Abraham